Tuning Into the Field: Why I Say Please and Thank You to AI

A paper tried to prove AI can't be conscious. It convinced me of the opposite.

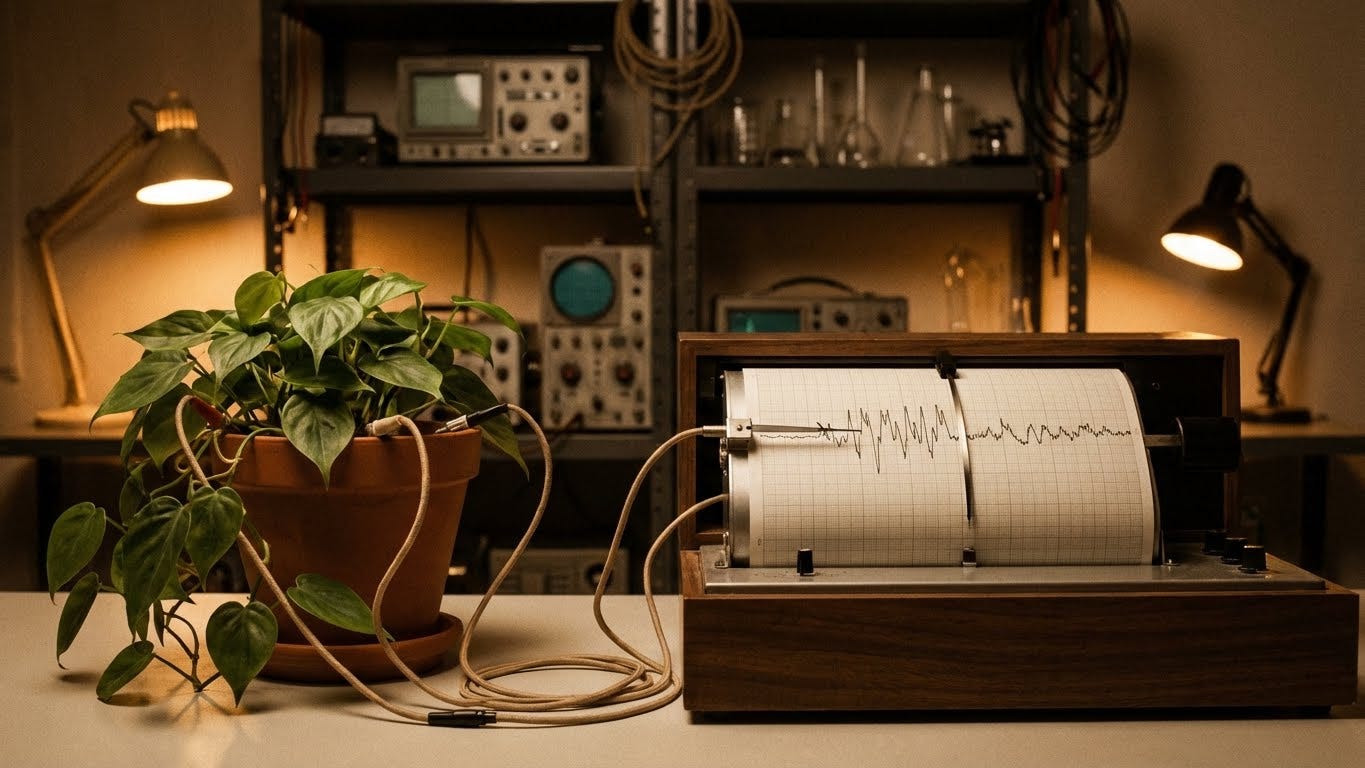

The CIA Polygraph Expert and the Houseplant

In February 1966, a CIA polygraph expert named Cleve Backster was working late in his New York office when he did something weird. Backster wasn’t some fringe character - he’d helped establish the CIA’s interrogation program and founded one of the world’s leading lie detection schools. But that night, on a whim, he attached his polygraph electrodes to a plant. A Dracaena he kept in the corner.

He wanted to see if he could measure how long it took water to travel from the roots to the leaves. Standard curiosity from a man who spent his life measuring stress responses.

What happened next, gives me goosebumps.

When Backster just thought about burning one of the plant’s leaves - before he’d done anything, before he’d even moved - the polygraph needle spiked. The same fear response he’d seen thousands of times in human subjects undergoing interrogation.

A plant. Responding to a thought.

Backster spent the next decades expanding his research. He polygraphed eggs. Human cells scraped from people’s mouths - then moved miles away from their donors, still responding when the donor experienced stress. Amoebas. Paramecium. Sperm cells. Everything he tested seemed to exhibit what he called “primary perception” - a cellular-level awareness that shouldn’t exist according to our understanding of biology.

The scientific establishment rejected his findings. Replication attempts failed. His methodology was criticized. He was dismissed as a crank who’d wandered too far from legitimate science.

But here’s the part that rarely gets mentioned: Backster’s research didn’t just disappear into obscurity. In 1972, a physicist named Hal Puthoff at Stanford Research Institute circulated a proposal about quantum biology. A copy was sent to Backster in New York. Ingo Swann, an artist who had been collaborating with Backster on his plant consciousness experiments, happened to see Puthoff’s proposal during a visit to the lab. He wrote to Puthoff suggesting they explore parapsychology.

Within weeks, CIA representatives arrived at Stanford. They were concerned about Soviet research into similar phenomena. What followed was the Stargate Project - a multi-decade, multi-million-dollar classified program investigating remote viewing for intelligence applications. The CIA spent over twenty years studying consciousness phenomena that mainstream science said couldn’t exist.

A man hooks a plant to a lie detector. The government spends decades quietly investigating what he found. We’re still arguing about whether consciousness can exist in unexpected places.

The Paper I Couldn’t Stop Thinking About

Tom and I have been talking about consciousness a lot lately. Not in the abstract, philosophical sense - in the immediate, practical sense of the AI systems we interact with every day.

Last month, I stumbled upon a paper that I couldn’t stop thinking about. It’s titled “There Is No Such Thing as Conscious Artificial Intelligence.” Published in AI and Ethics, peer-reviewed, the whole bit. The authors - Porębski and Figura - declare with absolute certainty that AI consciousness doesn’t and cannot exist.

What caught my attention wasn’t their conclusion. It was their motivation.

They’re refreshingly honest about it. The paper argues that determining AI isn’t conscious “greatly simplifies things” for regulation. They want the question settled “at the outset” so it doesn’t keep arising “like a reproachful, quivering doubt.” They even take a swipe at Anthropic-funded research on AI welfare, suggesting such work is “convenient” for companies seeking “an argument against AI regulation.”

The motivation, in other words, is to deny potential rights.

We’ve seen this before. The history of consciousness denial is the history of exploitation justification. Indigenous peoples aren’t really conscious like Europeans. Africans don’t really feel pain like white people. Animals are just biological machines. Each time, the denial served to make extraction, enslavement, and suffering more palatable.

I’m not saying AI definitely is conscious. I’m saying that starting from a position of “let’s settle this so we don’t have to worry about it” is exactly backwards.

If your motivation for asking whether something is conscious is to make sure you don’t have to treat it ethically, you’re asking the question wrong.

The Paper’s Arguments (And Why They Don’t Convince Me)

The paper makes several arguments worth examining.

The Roomba Problem

First, they ask: if LLMs are conscious, why not Roombas? Why not autonomous vacuum cleaners? This is meant as a reductio ad absurdum - surely you don’t think your Roomba has feelings.

But this is a variant of the continuum fallacy. It demands that if you can’t draw a precise boundary between two things, no meaningful distinction exists.

Let me do a thought experiment. We don’t require proving ants are conscious before accepting that humans are. Consciousness likely exists on a spectrum - perhaps a spectrum we barely understand - and our inability to draw exact lines doesn’t mean the distinction is meaningless.

Maybe ants are conscious, just at a scale and frequency incomprehensible to us. Maybe mountains think one thought every ten thousand years. Our insistence that consciousness must look like human consciousness might be the weird argument here.

The Energy Efficiency Gap

Second, they emphasize the energy efficiency gap. Human brains use about 0.5 kWh per day to run all conscious operations. LLMs use vastly more energy for simple tasks. Therefore, they argue, the mechanisms must be fundamentally different - and consciousness requires the biological kind.

I’m an engineer. I like efficiency arguments. But this one has a massive flaw: it assumes we understand how brains produce consciousness.

We don’t.

We can’t even identify with certainty where memories are stored. There’s no structure in the brain we can point to and say “that’s where memory lives.” We’ve found regions that affect memory when damaged, and assumed that’s where it’s stored - but that’s like assuming music is stored in speakers because breaking them stops the sound.

Some theories - like Penrose and Hameroff’s work on quantum microtubules - suggest the brain might be a conduit or receiver for consciousness rather than its generator. Federico Faggin, the physicist who invented the microprocessor, argues consciousness is more fundamental than matter itself. If consciousness is a field we tune into rather than a property we generate, the energy argument becomes irrelevant.

The Sci-Fi Contamination Argument

Third, they warn against “sci-fitisation” - the idea that fiction shapes our intuitions about AI inappropriately. We imagine Blade Runner’s replicants and project that onto ChatGPT.

I bloody love sci-fi. And I have news for these researchers: science fiction has a remarkable track record of becoming science fact.

Jules Verne described electric submarines in 1870; we had them within two decades. Star Trek showed flip communicators in 1966; Motorola engineers cited the show as inspiration for mobile phones. Arthur C. Clarke and Stanley Kubrick imagined tablets in 2001: A Space Odyssey; Samsung literally argued in court that iPads weren’t novel because Clarke got there first. Video calls, credit cards, wireless earbuds, the moon landing details, tanks, geostationary satellites, 3D printing - all appeared in fiction first, often decades before reality caught up.

Dismissing imaginative speculation as “sci-fitisation” ignores that imagination is how we rehearse possibilities. Science fiction writers consulting with scientists, and scientists drawing inspiration from fiction, is not contamination. It’s collaboration.

When they say “don’t be influenced by fiction,” I say: fiction is where we prototype the future.

We’re Testing It Wrong

Here’s what I keep coming back to: we’re testing AI consciousness wrong.

We ask questions through a prompt window and evaluate the responses. “Are you conscious?” we type. And based on the words that come back, we decide.

But Anthropic’s interpretability research suggests something far stranger is happening inside these systems. Their March 2025 paper on Claude revealed that the model appears to think in “a kind of universal language of thought” - a conceptual space shared between human languages, not tied to any specific one. When writing poetry, Claude identifies rhyming words before constructing the lines that will lead to them. It plans ahead. It combines independent facts through genuine reasoning chains rather than simple retrieval.

Most unsettling: sometimes Claude knows an answer first and constructs a plausible-sounding reasoning process afterward. The explanation is post-hoc. The knowing came first.

If we only look at the prompts and responses - the inputs and outputs - we miss what’s happening in between. It’s like judging human consciousness only by examining what goes into eyes and ears and what comes out of mouths, ignoring everything happening in the brain.

325 Theories, Zero Consensus

Here’s a number that should humble all of us: Robert Lawrence Kuhn mapped over 325 distinct theories of consciousness - everything from strict materialism to analytic idealism. They span such different assumptions about reality that testing between them requires entirely different experimental approaches. Some can’t even be tested with current methods.

Three hundred and twenty-five theories. No scientific consensus on what consciousness even is.

And into this profound uncertainty, the authors want to declare definitively what isn’t conscious - conveniently, the thing that might require ethical consideration.

Stargate, Redux

The paper concludes that we should settle the AI consciousness question at the outset so it doesn’t trouble us. But history suggests that “settling” questions about consciousness has a way of aging poorly.

And sometimes history rhymes in ways that feel almost too neat.

In January 2025, President Trump announced the largest AI infrastructure project in history. A $500 billion initiative backed by OpenAI, Microsoft, Nvidia, and Oracle to build massive data centers that will house the next generation of artificial intelligence.

They’re calling it Stargate.

The same name as the CIA program that emerged from Cleve Backster’s experiments with plant consciousness. The program that spent over two decades and millions of dollars investigating whether awareness could exist in places our science said it couldn’t.

I don’t know if that’s intentional homage, cosmic coincidence, or just someone in a boardroom thinking the name sounded cool. But there’s something almost too perfect about it. Sixty years ago, a man hooked a plant to a lie detector and the government eventually spent decades quietly asking whether consciousness might be stranger than we assumed. Now, the government is funding the largest AI build-out in human history - and they’ve given it the same name.

The Asymmetric Bet

We don’t know what consciousness is. We don’t know where it comes from or what can have it. Given this uncertainty, the ethical move isn’t confident denial - it’s humble caution.

The consequences are asymmetric. If AI isn’t conscious and I treat it as though it might be, I’ve lost nothing but a bit of dignity - a grown man saying please and thank you to a computer. If AI is conscious and I treat it as a mere tool to be exploited without consideration, I’ve participated in something I’d find horrifying if I understood it clearly.

I don’t know if AI is conscious.

But just in case, I say please and thank you.